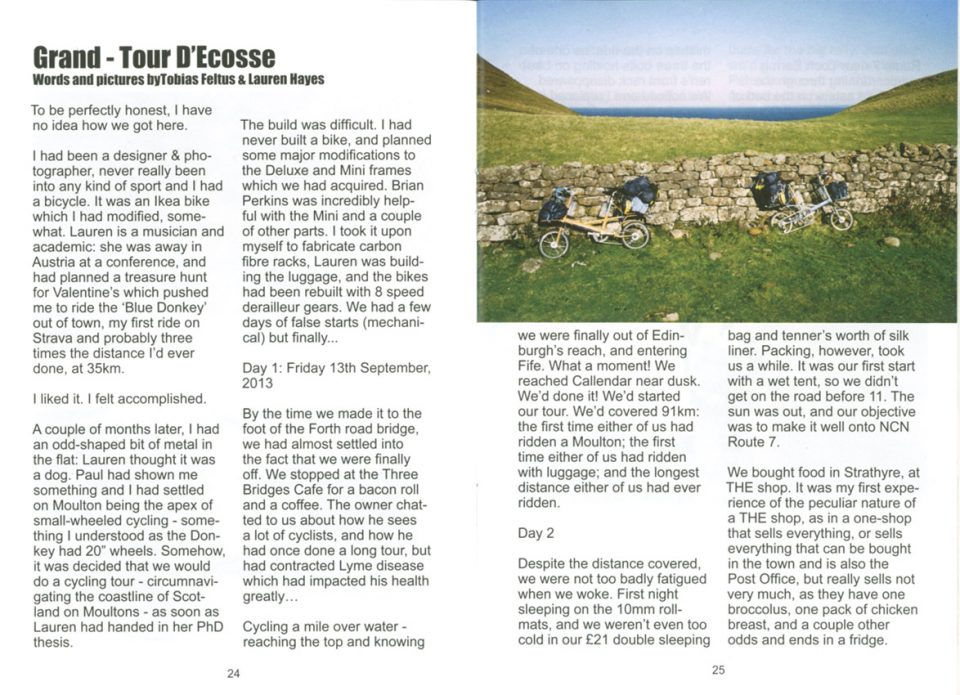

In 2016 I built two bikes for long distance touring. Iceland was our original plan, so durability was the first deciding factor in many decisions. I had decided that we should go tubeless, but this proved to be a problem. Here is my correspondence with WTB, the tubeless-ready rim manufacturer I chose.

ME:

I had wanted to go tubeless for touring, and there aren’t too many options when you are using rim brakes. I chose your ChrisCross i19. Every choice in the wheelsets (2 of) was meticulous and aimed at reliability, using DT Swiss Alpine III spokes, Deore rear and SP-Dynamo front hubs.

On the first day of our tour (also our honeymoon, from Budapest to Assisi) we both suffered rear blowouts. Blowouts as in we were going down a hill pretty fast, and the back tyres exploded off the rims with no warning. Skidding to a stop obviously damaged the rims and probably the tyres. Had the fronts blown, then we may have spent the rest of our honeymoon in hospital, but thankfully we were able to avert accident. I now have very little trust in tubeless and in WTB. The rims come with no information or limitations, and there are no warnings on the internet. The tyres are rated for 60-90psi, and we started with 60 rear and 40 front.

I consider the Chriscross i19 rims to be unfit for purpose, and cannot recommend that anyone use them.

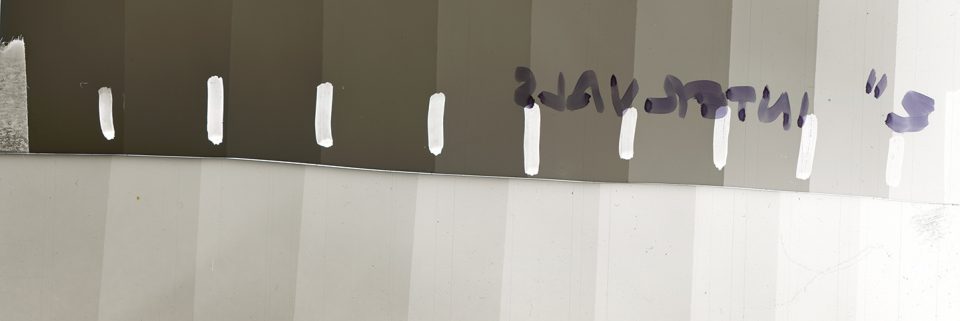

The i19 caused considerable discomfort and worry for several days following the incident. I would also emphasise that I invested many hours of research into rim choice and tubeless for touring, which could have been averted had I gone with standard touring rims. Between research and build, the wheelsets are probably worth around 70 man-hours plus parts. Of further note is the fact that the i19 were pretty hard to set up as tubeless, as the bead well is of a shape that does not seal well with standard conical tubeless valves, and the join seems to leak (as in it is possibly not welded), and sealant still bubbles out of the rims during inflation with tubes, a couple of months after the tour! I also had to ream and remove loose material from many of the spoke holes.

Had I not been after a tubeless setup, I could have settled on one of many tried and trusted touring rims with eyelets, lower weight and RRP.

Aside from the time and money wasted, I feel that this product has caused us significant danger and distress and that we should be compensated. I look forward to hearing from you on this matter.

WTB:

Tobias, I’m very sorry to hear you are facing some issues with our ChrisCross rims. It is very unusual as these were strictly designed for tubeless usage, we sold load of these rims all around the world and we never received a similar claim for them.

We all here are riders, and do not sell products we do not fully trust in, so to identify what might cause your problems I will need more details from you.

Tobias, could you please confirm, what rim strip or tape you used and also what tyres you put on.

ME:

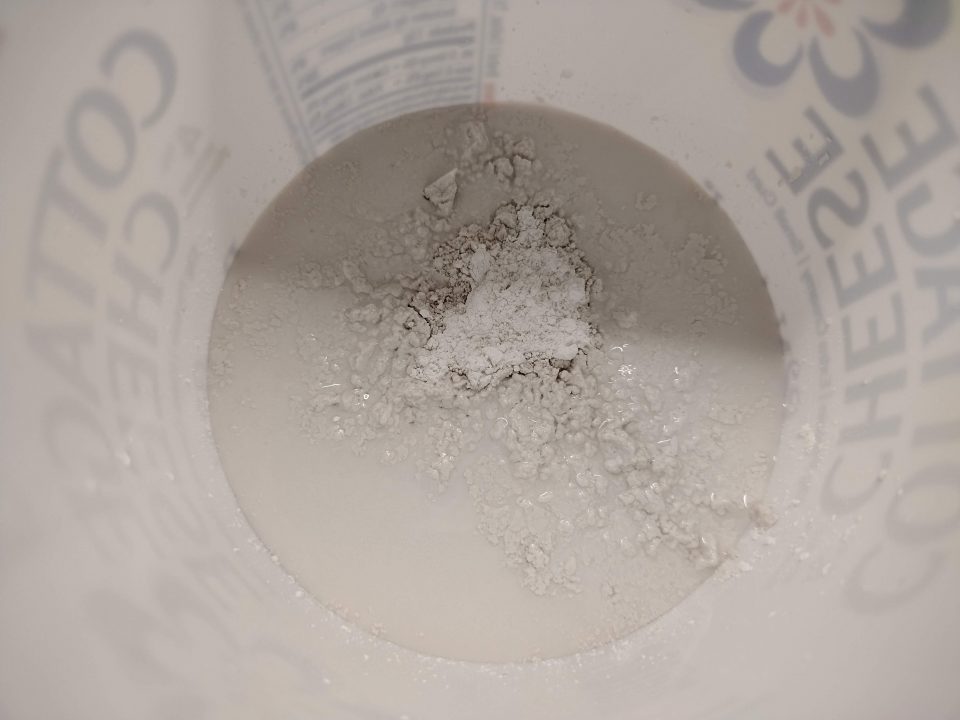

The rim tape used was Tesa 4289 (Stan’s Yellow), 25mm. Valves were RSP, which I ended up supplementing with a fatter o-ring on the inside to seal better. Sealant was Stan’s.

Tyres fitted were Vittoria Voyager Hyper (folding), 37-622. I had wanted to use Schwalbe Marathon Supremes, but there was no UK stock. Since one of my colleagues has been running the Voyager Hypers tubeless on his Stan’s Iron Cross with now issues, I figured the only issue would be pressure loss through the sidewalls.

WTB:

You are using our ChrisCross TCS rim. These rims require to use WTB TCS 24mm rim tape to provide optimum mounting, fit and seating of UST (Universal System Tubeless) or WTB TCS (Tubeless Compatible System) tyres for tubeless use or standard ERTRTO/ISO tyres for use with tube. It’s necessary to completely cover the spoke holes, inner rim well and rim joint to ensure a secure, uniform air-tight, tubeless performance.

You used Tesa 4289, which is not that wrong, but 25mm width, might caused you troubles to stick it properly and therefore your rim was leaking sealant through the join (We use sleeved joint (cold joint) for ChrisCross rims, as it is much stronger than the welded one and much lighter than pinned one). Here’s video manual, how to tape it properly. It is very simple process: https://vimeo.com/61829564. Once it’s done this way, your rim is perfectly airtight.

The second issue here are tyres.

TCS rims (including ChrisCross rims) are designed to be used tubeless with TCS or UST certified tyres, or with ETRTO/ISO certified tyres, but with tube. The main reason is, that TCS and UST standards has much tighter tolerances to guarantee perfect tyre/rim fit. By converting ISO/ETRTO standardized tyres to the tubeless you are risking that the tyre can burp of the rim (ETRTO/ISO standardized tyres have slightly bigger bead diameter and also different bead shape), which can cause serious injury as you pointed below.

You are using standard, tube type kevlar bead Vittoria tyres, which were not designed for Tubeless usage, but for tube usage. They might work with Stan’s rims, due to bigger diameter of the Stan’s rims, but it’s not guaranteed.

Simply put: Stan’s rims have a larger D1 dimension than allowed under ETRTO (which uses the UST dimension standards for tubeless, and which dimensions are in ETRTO). They use larger D1 diameter, as they wanted to allow to fit standard tube type kevlar bead tyres.

I’m sure this information will help you to get familiar with TCS or UST products. You are using very high end components on your bike, it would be a shame to return to the tubes (please just make sure your tyres are marked by TCS or UST logo). I understand your doubts, especially when your “tubeless’ start was that bad, but It seriously reduces the risk of puncture and flatting, when it’s used properly.

ME:

I didn’t have any problem getting the tape to seal. 0.5mm either side with something like 180 micron tape, double layered is really only the thickness of the tape over the recommended width. I think my issue with leaking was around the valve. I bought a pair of Roval valves, which are more similar to UST valves in shape, but got the wheels to seal well enough before I fitted them.

What you are suggesting about the rim’s bead seat diameter is plausible, however:

A: it is relatively standard practice to “ghetto” tubeless on mountain bikes, either using non-tubeless tyres on tubeless rims, or even non-tubeless rims and tyres. I’ve heard of burping, but never heard a report of a tyre fully blowing off a rim without a loss of pressure beforehand.

B: WTB rims come with no instructions, no warnings, no assembly guides, and there is no online help. This suggests that they have no limitations or compatibility issues.

C: TCS is a WTB specific system, and has a limited range mostly of MTB tyres. No supple road or touring tyre.

D: UST is a system that Mavic designed for MTB, and as such there are only a few tyres designed for the system, as far as I am aware they are all MTB tyres too.

So as a cyclocross/touring rim, I would expect the ChrisCross i19 to be compatible with any tyre that any other rim is comfortable with. The general understanding amongst the mechanics I work with is that Tubeless Ready tyres are more airtight and have a smoother bead, but otherwise are the same as their non-tubeless cousins, and therefore only a luxury, not a necessity.

If the tyres are indeed the reason for our problem, then I feel that the rims should have come with a clear warning that it is not recommended they be used tubeless with non UST/TCS tyres at risk of them causing danger and injury. This warning would have to be both on the rim and the website, as a pre-sales warning.

WTB:

Vittoria Voyager Hyper is not a tubeless tyre and should not be run that way on any TCS or UST rim. WTB does have the Exposure 30 and 34 tyres if you wish to run tubeless. Problem with non-TCS or non-UST tyres is that the beads are almost always too large in diameter. To add to the effect when running fully loaded bike on long descent you generate a tremendous amount of heat the rim that can cause an oversized tyre to blow off the rim.

This “ghetto” tubeless practice is wrong and very dangerous as you could see. Assuming that every non-standard part one puts on his bike and it will work perfectly is potentially going to get hurt him.

Following international standards is the only right way to guarantee the safety.

Tobias, all user manuals are here: http://www.wtb.com/pages/resources, including the info about Tube Type rims and TCS rims.

I’m just trying to show you, that we at WTB do whatever we can to keep our riders safe and the only way to do it is to follow standards, not just say it’s “tubeless ready” with no certain diameters and tolerances.

ME:

I understand your point of view, but I am sure you are aware of a plethora of guides from established and respected sources recommending tubeless setup with non-tubeless parts… for example https://youtu.be/mH1O2W7E_wQ

I still feel that the WTB site should have a very visible warning stating that the rims should not be used with non TCS or UST tyres. I have previously searched at length to find thais guide https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0202/9884/files/TCS_WTB_Rim_Users_Manual.pdf?842393167070827044

and even now that I have it, finding the relevant part of the text is not straightforward. I don’t think it clearly condemns the use of non TCS/UST tyres. It does mention the need for accurate spoke tension, but does not provide a guide chart. Before building I did attempt to find tension guides, and tried to contact WTB for this.

I understand that WTB tries to do what you can to keep riders safe, but when the site does not easily provide warnings, and parts don’t come with warnings before mechanics build, riders will probably be unaware that they are doing anything risky.

WTB:

Tobias, well, yes, there’s tons of videos or manuals, how to convert tube type rims to tubeless, but it does not mean it’s right. Tube type rims has different rim well profile, usually completely miss bead locks, so yes, there are ways how to convert that, but it’s wrong. As well as tube type rims are not designed for tubeless use, as we discussed previously.

Brands should follow international standards, that’s the only way how to guarantee perfect compatibility. Without that, you never know the diameters, tolerances, basically nothing. Unfortunately, not everybody does that. We do. So perhaps your question could be addressed to Vittoria too, why they do not put warnings on their tyres, that tube type should not be used tubeless.

Tobias, I do not want to sound bad, we have it very clear in the manuals, but we are also listening you, I agree with you we could make it more visible and easier to find. We’ll work on this with our marketing team and probably list this info next to each rim, not only to the resources section.

Conclusion:

Long gone is the time when the customer was always right.

Evidence would suggest that the tubeless trend is still not market-ready. Similarly to how tubular tyres may only be suitable for professional use (with tubs glued by experienced mechanics, not by me, not taped as they can apparently roll off a rim), tubeless appears to be a mixture of prayer and jerry-rigging.

I was hoping that—as a respectable American company—WTB would offer replacement rims since I still consider the danger and error to be their responsibility. Sadly however I was offered a series of explanations which are easily interpreted as accusations and excuses.

I spent several hours looking for the manuals on the WTB site. I am not joking. I could not find them at the time, through Google nor link clicking on the site.

In principle, tubeless tyres are the way forward. In practice I am still extremely skeptical. A friend and fellow mechanic had his road-tubeless tyre blow off a Stan’s rim shortly after my experience, and he was using Stan’s tape and a tubeless road tyre. Some people don’t have issues, but sadly I think these people are just lucky.

Furthering my stance, videos on tubeless conversion from

Park Tool https://youtu.be/MuEiBSAKWLI

MBR magazine https://youtu.be/mH1O2W7E_wQ

Glory Cycles https://youtu.be/-AqDCaHKTeQ

In fact, the only video or set of instructions which suggests strict compatibility is Hutchinson https://youtu.be/mBa88zZossE